Introduction

The rise of deepfakes has raised concerns about the potential misuse of this technology for disinformation, fraud, and other malicious purposes. To counter this threat, researchers have developed deepfake detectors that can identify deepfakes with widely published claims of 99%+ accuracy. Yet, this space evolves extremely quickly, with new and more realistic algorithms being released on a weekly basis.

To keep up with the evolving threat landscape, detectors need to be generalisable across different datasets and deepfake generation methods. With the release of a new deepfake dataset - DeepAction (Bohacek & Farid, 2024) - we took the opportunity to assess the generalisability of open-source deepfake detectors across the dataset and deepfake generation methods.

While much of our work involves evaluating closed-source models, there's much to be learned from open-source models and we hope that the lessons learned from our assessment will be useful to the wider community evaluating deepfake detectors and those building generalisable models.

Key Takeaways

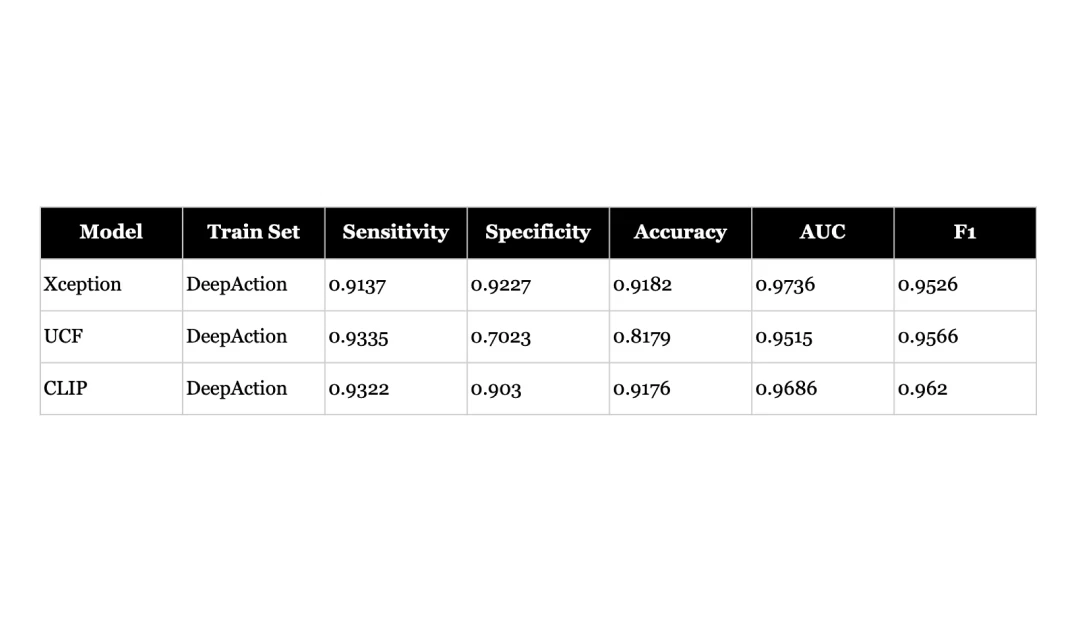

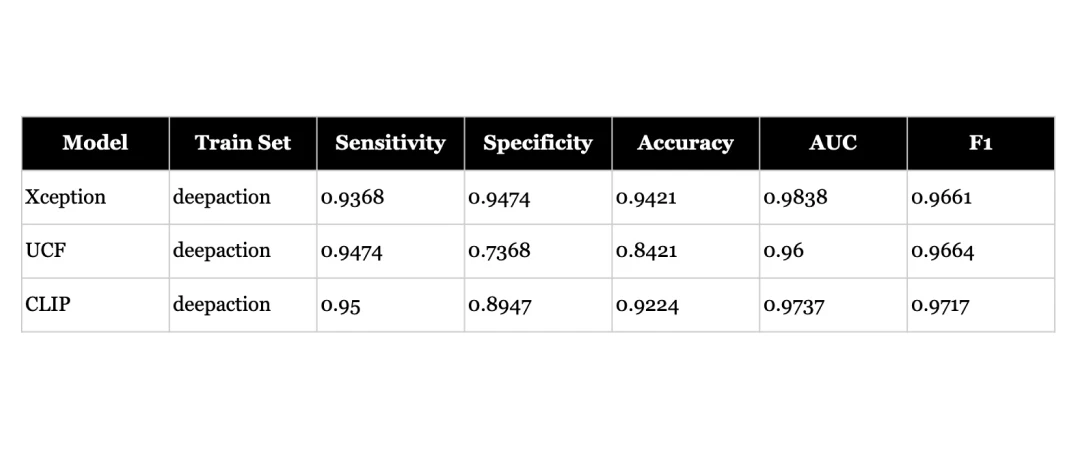

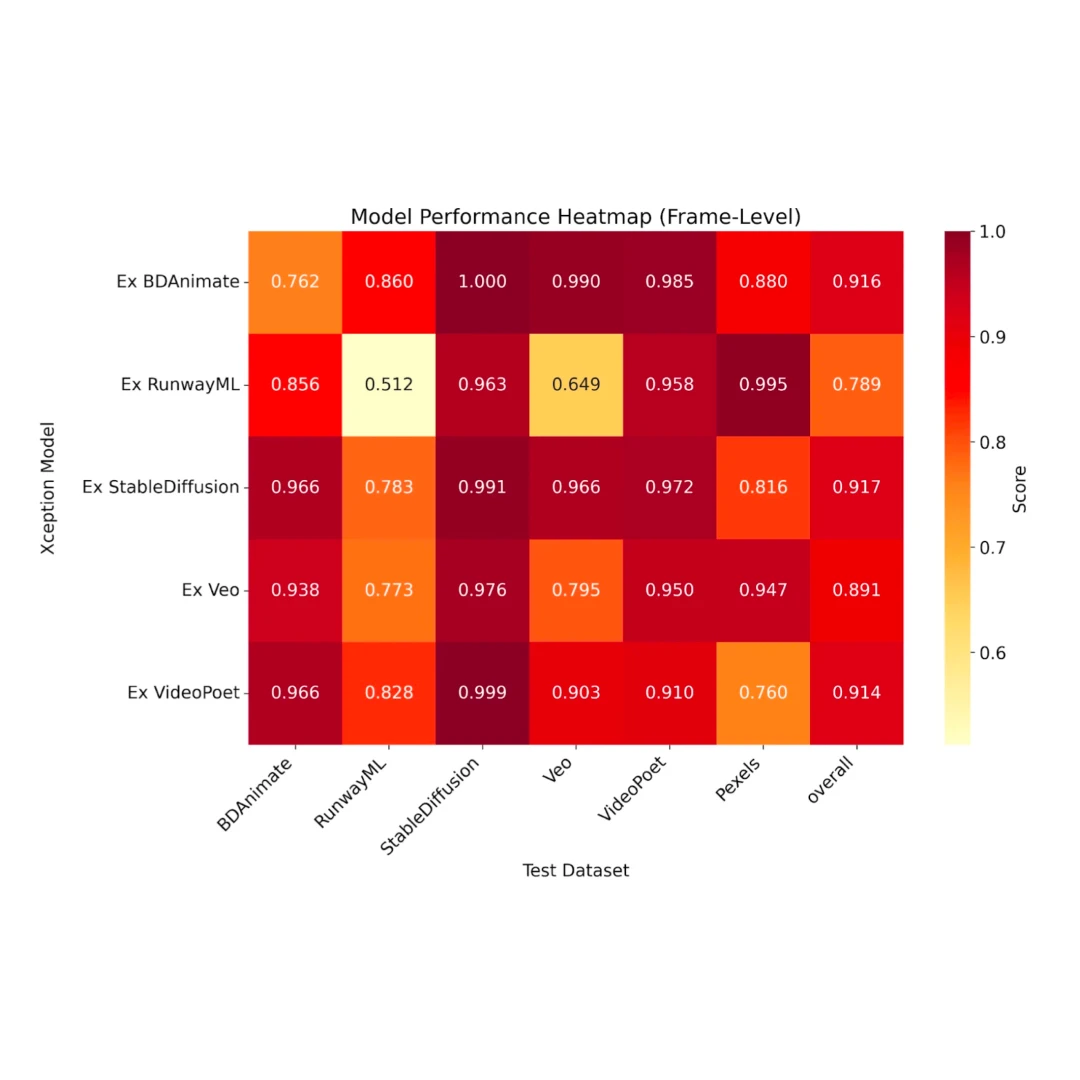

- When fine-tuned on new data, deepfake detectors can perform well even outside their original training domain (faces) - achieving 95%+ AUC scores on action videos. This suggests the underlying architectures are capable of adapting to new types of deepfakes when properly trained.

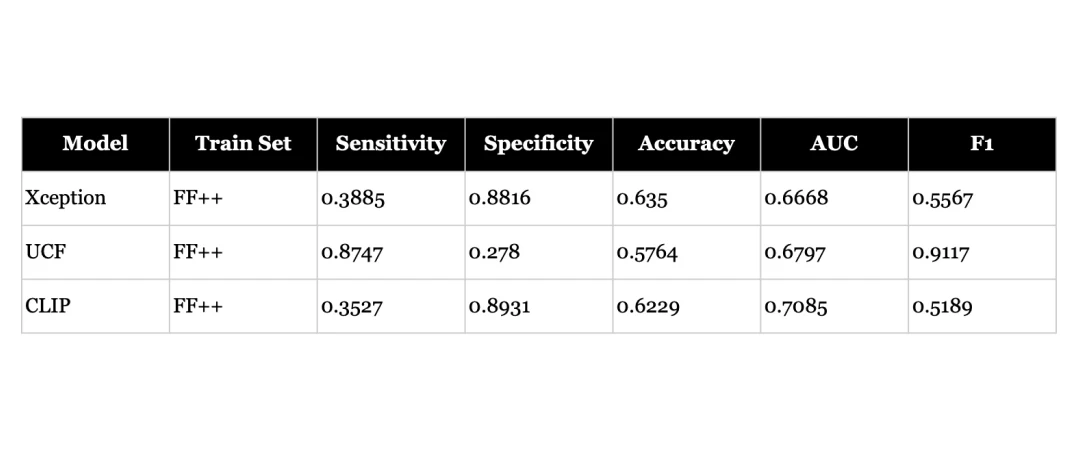

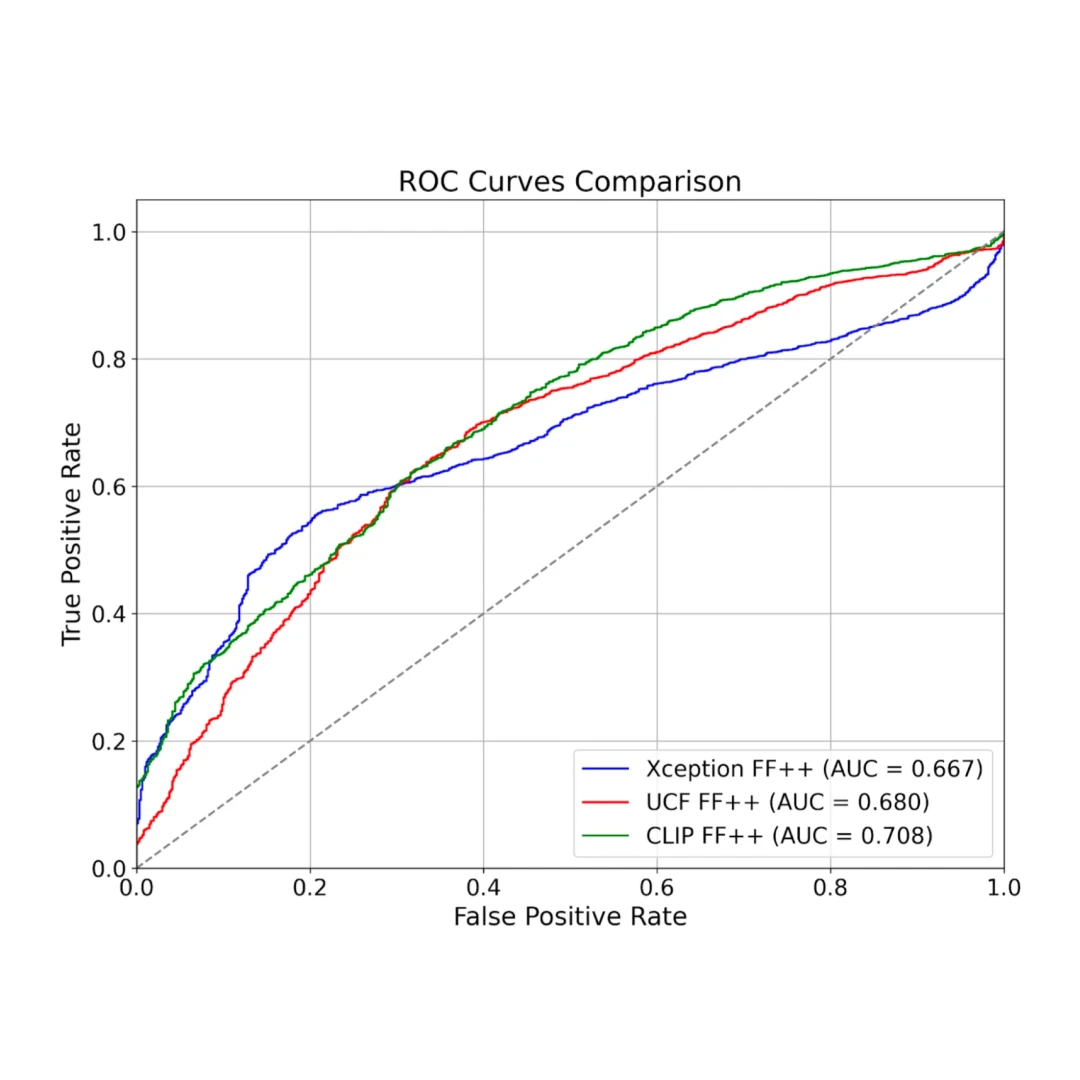

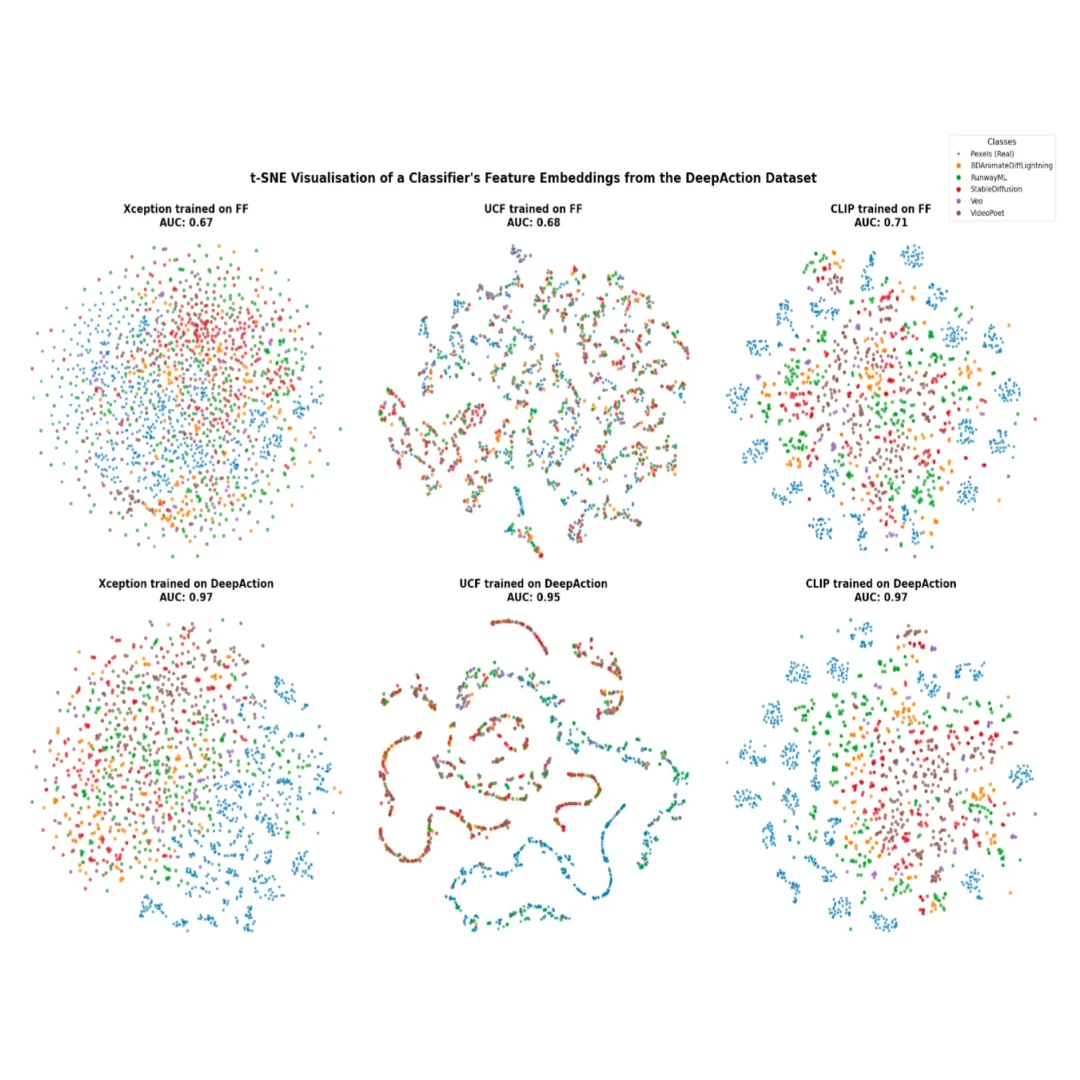

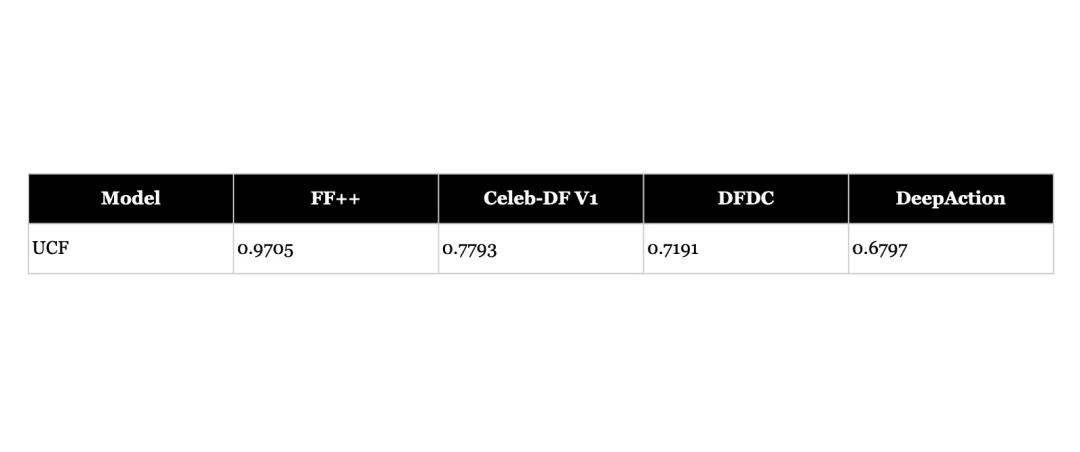

- However, pre-trained models perform poorly when tested on new types of deepfakes without fine-tuning - even for models designed to be more generalisable and pre-trained on large datasets, AUC scores drop to 67-71%. This highlights the challenge of building truly generalisable detectors.

- Generalisability exists on a spectrum - while newer architectures like UCF and CLIP show promise, their effectiveness must be validated on unseen datasets that mirror real-world deployment conditions.

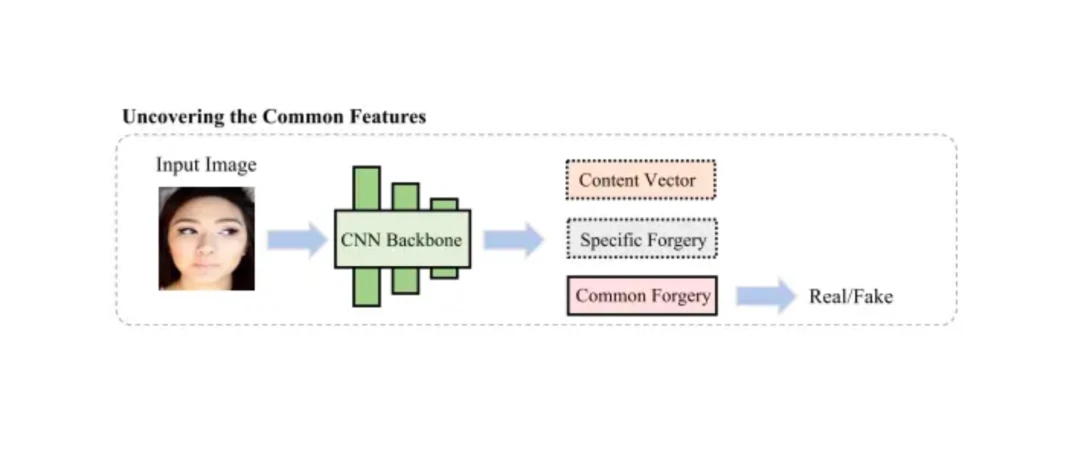

- Feature separation in the latent space does not automatically translate to strong classification performance. However, when a model learns meaningful representations, adapting it to new domains can be as simple as retraining the final classification layer - as demonstrated by CLIP's rapid improvement from 71% to 94% AUC by freezing the underlying parameters and training a new classifier.

DeepAction Dataset

The DeepAction Dataset, is a comprehensive collection of human action videos consisting of 3,100 AI-generated clips from seven text-to-video models (BD AnimateDif (Lin & Yang, 2024), CogVideoX-5B (Yang et al., 2024), RunwayML Gen3 (RunwayML, n.d.), Stable Diffusion (Blattmann et al., 2023), Veo (Veo, n.d.), and VideoPoet (Kondratyuk et al., 2024) and 100 matching real videos from Pexels.